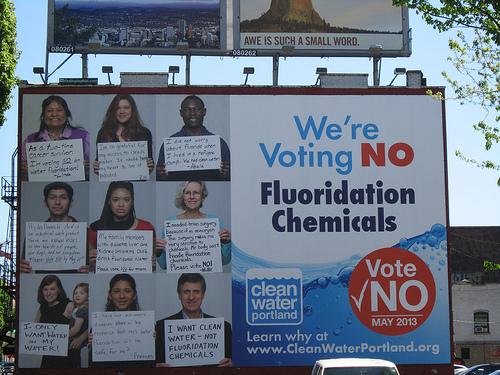

This week, there was great news from Portland, Oregon: Voters had overwhelmingly rejected fluoridation, 60% to 40%. Although pre-election polls had shown fluoride losing, enough people remained undecided that, considering margin of error, the vote could have gone either way.

This week, there was great news from Portland, Oregon: Voters had overwhelmingly rejected fluoridation, 60% to 40%. Although pre-election polls had shown fluoride losing, enough people remained undecided that, considering margin of error, the vote could have gone either way.

“This is not just Portland,” a member of the anti-fluoride campaign told KATU News.

This is nationwide….[W]hat happened in Portland, what is happening here and now, is going to have nationwide and worldwide ramifications.

Something else besides the quality of Portlanders’ drinking water remains unchanged: When you weigh the presumed benefits against known risks – to individual and environmental health – fluoridation is just bad policy. As Dr. Glaros wrote a while back, it’s “forced medication without representation.” In the words of Dr. Anne Marie Helmenstine, “Even if it was beneficial, fluoridation isn’t something you get to choose or not choose. This is my bottom-line reason for opposing fluoridation.”

Those who want fluoride can get their fill with toothpastes, rinses, conventional dental treatments and the like, though it’s actually not essential for healthy teeth. In fact, all of the things it’s said to do – remineralize, inhibit demineralization and repel bacteria – can be done through nutrition and hygiene, no toxins necessary. The later research of Dr. Weston Price demonstrated as much – and paved the way for the complex understanding we have today of the relationship between diet and dentition.

Meantime, recent research has called into question some of the conventional wisdom about how fluoride works. A couple years ago, there was the American Chemical Society (ACS) paper we told you about before, which found that while fluoride creates a “protective layer” over the teeth, it’s up to 100 times thinner than imagined.

It would take almost 10,000 such layers to span the width of a human hair. That’s at least 10 times thinner than previous studies indicated. The scientists question whether a layer so thin, which is quickly worn away by ordinary chewing, really can shield teeth from decay, or whether fluoride has some other unrecognized effect on tooth enamel.

Three of those scientists were involved in a fluoride study published last month in the same ACS journal. This paper provides

new evidence that fluoride also works by impacting the adhesion force of bacteria that stick to the teeth and produce the acid that causes cavities. The experiments performed on artificial teeth (hydroxyapatite pellets) to enable high-precision analysis techniques revealed that fluoride reduces the ability of decay causing bacteria to stick, so that also on teeth, it is easier to wash away the bacteria by saliva, brushing and other activity.

Fascinating stuff, yet there are safer substances – cranberries and xylitol, to name two – that have also been shown to keep bacteria from clinging to the teeth. Again, we’re faced with the question: When you can do something in a way that’s non-toxic and able to work with the body instead of against it, why opt to do it with a poison? You gain nothing except a heavier toxic burden on the body.

Earlier this spring, we looked at how perfectly your teeth are designed to protect themselves from enamel damage and decay. We just need to treat them right: eat healthfully, stay active, minimize toxic exposures, manage stress, get sufficient rest and quality sleep, and practice good, regular hygiene. Ninety-eight percent of the time, problems crop up only when we treat our teeth poorly. Then, we have a choice: Start treating them better or throw drugs or some other medicament at them in hopes you can neutralize the damage even if you go on making the same poor choices.

We know which seems the more rational.

Image by Neal Jennings, via Flickr