Choose the right words, and you can make most anything seem better than reality. A cramped, shotgun shack gets turned into a “cozy cottage.” Mercury amalgam gets spun into “silver fillings.”

Now the USDA is getting into the act with its proposed rules for GMO labeling. If they get their way, we’ll be saying “goodbye” to genetically modified organisms. They’ll be called “bioengineered food” instead.

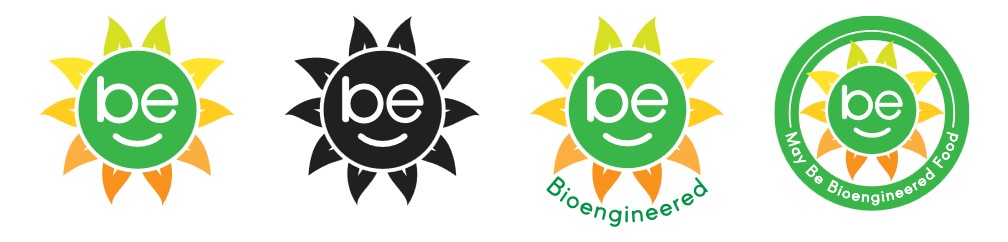

But that’s just the start of what the executive director of Food & Water Watch calls “a gift to industry.” You’ve got to see the labels:

And that’s just one version of it. (You can see them all at the link above.)

The colors, the smiley faces, the suggestions of nature – these all suggest an environmental friendliness that isn’t necessarily the reality when it comes to GMOs.

For despite what the ag corporations tell us, recent research suggests that GMOs aren’t necessarily equivalent to naturally grown foods. Here’s what lead author Dr. Michael Antoniou had to say about his recent study comparing GMO and non-GMO corn:

The establishment of substantial equivalence is a foundation for safety evaluation of GMO crops. In the United States and in other countries, the crops that have been commercialized are claimed to be substantially equivalent to non-GMO equivalents, and therefore safe.

But the kind of compositional analyses done thus far to see if a GMO crop is substantially equivalent is a crude nutritional analysis of total protein, fats, and vitamins.

If you use cutting-edge molecular profiling methods as we did, they will provide a spectrum of different types of proteins and small molecule metabolites. It’s a very in-depth analysis.

Does the claim of substantial equivalence stand up to this fine compositional ? No, it doesn’t. Our analysis found over 150 different proteins whose levels were different between the GMO NK603 and its non-GMO counterpart. More than 50 small molecule metabolites were also significantly different in their amounts.

“Once you do a compositional analysis properly,” he says, “the GMO corn doesn’t stand up to claims of substantial equivalence.”

Maybe the creepiest aspect of the proposed labels is the version that says the product “may be bioengineered food.” Maybe it is. Maybe it isn’t. Who knows?

But as we’ve noted before, we, as consumers, have a right to know what’s being sold to us so we can make an informed decision whether to buy or not. Most of us are so distant from the actual sources of our food, we must depend on the producers and manufacturers to be upfront, honest, and clear about what they’re providing.

These proposed labels work against that.

The good news? They’re not a done deal yet. The proposed rule– which you can learn even more about here – is now open for comment and will be through July 3, 2018. You can submit your comments here.