A few years ago, a group of researchers decided to look at the relationship between patient satisfaction and their experience in the health care system. They found that those who were most satisfied also received more treatment, took more prescription drugs – and were more apt to be dead within a few years.

Clearly, more medicine isn’t better medicine.

The point was made more recently by a study of heart patients in teaching hospitals:

A new study shows that 59 percent of cardiac arrest patients admitted to teaching hospitals died within 30 days when their doctors were away at cardiology conferences; 69 percent died when doctors were in the office. Patients suffering from heart failure had similar outcomes. The results, which appear December 22 in JAMA Internal Medicine, show that high-risk patients have fewer intensive procedures when their doctors are away, suggesting such procedures may do more harm than good.

While these findings are particular to just one class of patient, plenty of research over the past few years confirms that medicine-as-usual can be risky business indeed. A 2013 study in the Journal of Patient Safety found that medical errors are the third leading cause of death in the US, with as many as 440,000 deaths every year due to some preventable harm occurring during their time of care. A hundred thousand Americans die each year due just to “side effects” of pharmaceutical drugs.

Those deaths didn’t happen because the doctor made a mistake and prescribed the wrong drug, or the pharmacist made a mistake in filling the prescription, or the patient accidentally took too much. Unfortunately, thousands of patients die from such mistakes too, but this study looked only at deaths where our present medical system wouldn’t fault anyone. Tens of thousands of people are dying every year from drugs they took just as the doctor directed.

Research published in JAMA has estimated more than 2 million drug-related injuries to Americans each year.

More “medicine” is probably the last thing we need. What we do need is smarter medicine.

And smarter dentistry.

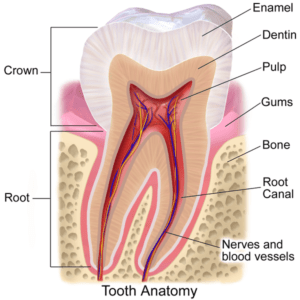

Teeth aren’t hard, lifeless structures that you can just do things to without affecting the rest of the body. Each is a living organ. Underneath that hard, protective enamel is the softer dentin, made of miles of microscopic tubules through which nutrients circulate. They also contain a cell extension known as an odontoblast process, which helps keep the tooth well mineralized. (Odontoblasts are cells that form tooth tissue.) Within the dentin is the delicate pulp, full of nerves and blood vessels, living connective tissue and odontoblasts.

Teeth aren’t hard, lifeless structures that you can just do things to without affecting the rest of the body. Each is a living organ. Underneath that hard, protective enamel is the softer dentin, made of miles of microscopic tubules through which nutrients circulate. They also contain a cell extension known as an odontoblast process, which helps keep the tooth well mineralized. (Odontoblasts are cells that form tooth tissue.) Within the dentin is the delicate pulp, full of nerves and blood vessels, living connective tissue and odontoblasts.

Any time “work” is done on a tooth – say, a filling is placed – the whole tooth experiences trauma. Veteran biological dentist Dr. Gary Verigin provides an excellent description of what happens under the drill:

When a dentist drills a tooth, heat is created from all the friction. Though it will be cooled some as water or air is applied, quite a bit of heat remains. Moreover, the spinning of the carbide- or diamond-tipped bur creates a vortex similar to a tornado. This can – and does – suck out the protein processes that are within each dentinal tubule. Such empty tubules are called dead tracts. Repeated dental treatments, such as filling or crown replacements, thus become more detrimental to pulpal health. Eventually, this tooth meets the same fate as the toxicated tooth described above, again leading to a root canal.

Or extraction.

Either way, too much treatment can eventually kill the tooth.

Another thing to remember is that a filling – at least in an adult tooth – is never a one-shot deal. Eventually, all dental restorations must be replaced. Repeat trauma is guaranteed. (And let’s not forget the financial “trauma” of all this dentistry. It’s been estimated that each tooth that is repaired will cost over $2100 to maintain over a lifetime.)

Biological dentistry recommends a much more conservative approach. Instead of immediately reaching for the drill at the first sign of decay, we might take a wait-and-see approach, while coaching our patient toward better home hygiene and nutritional changes to support the health of the tooth. If the decay is in its early stages, light and on the surface, we might use micro air abrasion to remove it – basically, sand-blast it away. Ozone therapy might also be used to stop the disease process.

Biological dentistry recommends a much more conservative approach. Instead of immediately reaching for the drill at the first sign of decay, we might take a wait-and-see approach, while coaching our patient toward better home hygiene and nutritional changes to support the health of the tooth. If the decay is in its early stages, light and on the surface, we might use micro air abrasion to remove it – basically, sand-blast it away. Ozone therapy might also be used to stop the disease process.

Often, such measures are enough. All of them respect the natural strength and integrity of the tooth. Only if such measures fail do we consider more invasive treatments, such as a filling or crown.

And when we do go that route, we make sure to do proper biocompatibility testing in advance to make sure there will be no adverse effects from the materials we use to restore the tooth.

For we’re concerned with more than just the teeth. We understand the teeth, gums and other oral structures in their physical and energetic relationships with the rest of the body. We understand that the vast majority of health issues cannot be reduced to one cause-one effect; that a systems-based approach to health is required for optimum wellness. It’s the essence of holism.

Learn more about minimally invasive dentistry.

Tooth image by Bruce Blaus, via Wikimedia Commons