Choosing which materials to use to repair, replace, align or cosmetically enhance teeth isn’t a simple matter. In each case, the dentist has to consider a wide of factors related to where and how they’ll be used.

Bicompatibility is also a fundamental concern, at least to the biological dentist. While there are some materials, such as zirconium, that are considered broadly biocompatible – safe to use on nearly everyone – each person is biochemically and bioenergetically unique. Each has their own history of illnesses, dental and medical treatments, environmental exposures and so on – factors that have worked together to generate their current level of health or illness.

Bicompatibility is also a fundamental concern, at least to the biological dentist. While there are some materials, such as zirconium, that are considered broadly biocompatible – safe to use on nearly everyone – each person is biochemically and bioenergetically unique. Each has their own history of illnesses, dental and medical treatments, environmental exposures and so on – factors that have worked together to generate their current level of health or illness.

Because of this, we insist that all patients undergo biocompatibility testing when they come to our office for dental care.

Of course, there are some materials that are biocompatible for exactly no one. Their toxic potential far outweighs any presumed benefits. Mercury amalgam is one. Nickel is another.

So how about bisphenol A (BPA)?

This chemical compound is common to many brands of composite, the material used to make tooth-colored fillings, and since we first blogged about it, we’ve had a lot of follow-up questions. Increasingly, new patients come in wanting to know about how concerned they should be about BPA in their fillings. Although we’ve provided additional info here in the comments section, we know not everyone reads comment threads. So we thought we’d take some time to further discuss the issue here.

Our preferred method for determining biocompatibility is EAV, which is extremely sensitive and allows us to test a patient’s reactivity to virtually any substance. Just as accurate is serum (blood) testing, which many biological dentists rely on alone or in tandem with other testing methods. (You can read about the major testing protocols here.) For instance, the Clifford Materials Reactivty Test analyzes a blood sample for antibodies formed against 94 chemical groups and compounds. More than 16,000 materials are screened, as well as byproducts they release, to determine which products a patient may react negatively to.

BPA is one of the compounds they test for.

According to materials provided by the test’s developer, Walter Jess Clifford, there are just over half a dozen composites that their manufacturers say are “free of Bis-Phenol A in any form, whatsoever, bound or unbound.” That means that they are also free of bis-GMA and bis-DMA – chemicals from which BPA may be released. These products are:

- Diamond Crown

- Diamond Flo

- Diamond Link

- Venus Diamond

- Venus Diamond Flo

- Venus Pearl

- Visalys Temp

Other composites are claimed “to be free of dissociable, easily released or ionizable BPA.” They may still contain bis-GMA or bis-DMA, though “in fairness,” Clifford notes the amount of energy needed to release the sequestered BPA is “not usually commensurate with life.”

- Admira

- Clearfil

- Concise

- Esthet-X HD

- Filtek Supreme

- Filtek Supreme XT

- Filtek Z-250

- Grandio SO

- Herculite XR

- Kalore

- Point 4

- Premise Indirect

- Vertise Flow

- Z-100

It’s important to remember that composite is not the only BPA-free restorative alternative to amalgam. Neither ceramic nor porcelain contains the chemical. While these aren’t suitable for direct fillings, they are often ideal for indirect restorations such as inlays and crowns.

But what if you already have composite fillings that in all likelihood contain BPA?

Unlike mercury fillings, which constantly release mercury vapor after they’re placed and allegedly “stable,” BPA release from composite does not appear to be an ongoing thing. Research has shown that the greatest release comes soon after the material is placed, with no BPA detectable in saliva after 24 hours. As Clifford describes it,

We note that humans with normal and adequate metabolism are usually capable of glycouronating [sic] any BPA and facilitating its elimination via urine or stool. On the other hand, rodents such as mice, rats, guinea pigs and the like do not have this metabolic capability and rodent model is where the large majority of studies with BPA have been done. Whether the extrapolation of rodent data against BPA in humans if fully valid or not remains to be worked out. In the meantime, many have chosen to simply avoid BPA for themselves and their children as a simple precautionary measure.

In other words, under normal conditions, our bodies are able to clear BPA pretty well – presuming that the exposure is not ongoing. Unfortunately, we live in a world where BPA is still widely used, despite concerns about its impact on health and the environment. Daily BPA exposure from consumer products is far higher than the limited one time exposure shortly after the placement of a composite filling – especially if recommended safety protocols are followed.

Too often some people get extra worried about their composite fillings once they’ve learned a little about the BPA issue. Some go so far as to consider having them removed and replaced. Based on the current evidence, we believe that would be overkill. As mentioned, if the dental work involved isn’t causing any immediate health problems that either you experience or are detected through EAV or other testing techniques, removing the composite is apt to do more harm than good. The trauma each tooth would undergo through the removal process would weaken it. The more work done, the weaker it becomes …until it becomes a candidate for root canal therapy (according to orthodox dentistry) or extraction.

To learn much more about BPA and related compounds in dental work, we strongly recommend this presentation Clifford made to the IAOMT in St. Louis a few years ago:

Our thanks to Jess Clifford for materials used in writing this post – and, of course, for the marvelous work he has done and continues to do for biological dentists everywhere.

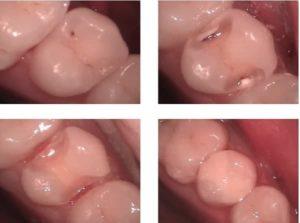

Image by Dental School Professor, via Wikimedia Commons