At their recent meeting, the ADA made a big to-do over the 70th anniversary of fluoridation.

“This is the most effective weapon in dentistry, I believe, to prevent not only tooth decay but mouth disease in general and overall health,” stated Raymond Gist, DDS, past ADA president, in a press release.

Quite a claim about a practice for which there is “very little contemporary evidence,” according to a study published earlier this year in Cochrane Reviews.

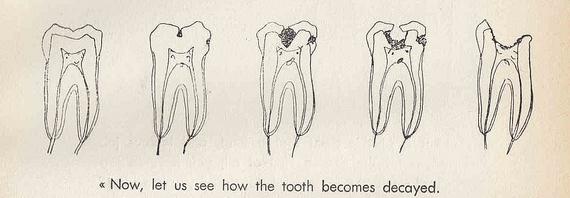

And as a new paper in the Journal of Dental Research indicates, the current state of dental health certainly doesn’t support such an extreme claim. Caries (tooth decay) persists and generally progresses over a lifetime.

Despite the wide-scale use of fluoridated toothpaste and consumption of fluoridated water by 66% of Americans since the 1960s, adults aged 65-74 y had an average DMFS [decayed, missing or filled tooth surfaces] of 70 [out of a total of 88] (Dye et al. 2007). Thus, although fluoride reduces caries, unacceptably high levels of caries in adults persist in all countries, even where there is wide-scale water fluoridation and the use of fluoridated toothpastes (Dye et al. 2007).

This is the case even among those who were relatively caries-free in their youth.

The embrace of fluoride is just one of several “misdirected strategies” that the authors point out. It distracts us from the undeniable root cause of caries, the factor without which it would not exist: sugar.

Without sugars, the chain of causation is broken, so the disease does not occur (Sheiham 1967). So, it is clear that sugars start the process and set off a causal chain; the only crucial factor that determines the caries process in practice is sugars. The other factors [commonly cited to suggest that caries is a multifactorial disease] are additional factors that alter the primary effect of sugars, not alternative contributors (Sheiham 1987; Scheutz and Poulsen 1999)….

So why call caries an infectious transmissible disease when the presence of…microorganisms in the mouth is ubiquitous and it is only the addition of sugars that then stimulates their proliferation and adhesive qualities and allows them to produce the acids required for dental caries?

Why, indeed?

It’s hardly news that the sugar industry, along with food product manufacturers and providers, have played a big role in both saturating our diet with sugar. Nor is it news that “Big Sugar” deliberately interfered with the making of public dental health policy decades ago – at least not since important research published earlier this year in PLOS Medicine showed how industry shifted the emphasis from addressing the cause (sugar) to trying to limit its damage through things like fluoride, sealants and even vaccines. Manipulations of both science and public opinion have been critical to increasing our sugar intake. (Such machinations are also the subject of a new documentary now making the festival circuit, Sugar Coated.)

It’s also hardly news that decay is, in the phrase of Dr. PJ Stoy, a “disease of civilization.” And though it was Weston Price who most famously and thoroughly showed the damage the modern Western diet can do to teeth and jaws, it’s not as though no one had noticed the detrimental effects of sugar before. As Stoy noted back in 1951, for instance,

Sugar, particularly, has been incriminated, since a rise in its consumption roughly parallels the incidence of decay and its use as an article of diet goes much further back in history than the introduction of refined white flour. From the early 1400s consumption in England was steadily rising, particularly among the wealthy classes. A German visitor in England in 1598 suggested that bad teeth were common enough at that time amongst those who could afford sweet meats, and also comments on their “black teeth” – “a defect,” he says, “the English seem subject to from their too great consumption of sugar.” To cane sugar was soon added beet sugar. Although its presence was known as early as 1605, it was not extensively extracted until the days of Napoleon, when the cutting off of all trade by the English blockade forced the Continental countries to find another source. This development of the beet industry further encouraged sugar consumption during the nineteenth century to such an extent that it has now become a main item of the modern diet. In 1930, for instance, the consumption per head per year in the United States was 125 lbs. – 2 ½ lbs. per person per week!

And today, we eat even more – up to 170 pounds (or even more!) a year; an average of 22 teaspoons a day, or triple the recommended max daily intake. It’s not just from the obviously sweet stuff like cookies and candy and cake. Most hyper-processed foods contain at least some sugar – sometimes a lot – even organic brands. Sugars are also common in ready-to-eat meals, fast food and restaurant meals.

Not only are sugars – and white flour – damaging on their own. They also tend to displace other nutrients that could counteract at least some of their pernicious effects.

Happily, it seems that the tide may finally be turning. More people are becoming aware of the damage sugar can do and are trying to lower their intake accordingly. Increasingly, you hear that Big Sugar is the new Big Tobacco.

We all know how things turned out for them.