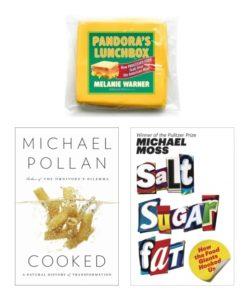

Three fascinating books about how food is prepared – whether by ourselves or global corporations – hit the market earlier this year. We think all three are worth your while, especially if, like most of our patients, you care deeply about how you feed your body, as well as your mind and spirit.

Three fascinating books about how food is prepared – whether by ourselves or global corporations – hit the market earlier this year. We think all three are worth your while, especially if, like most of our patients, you care deeply about how you feed your body, as well as your mind and spirit.

The first of these is Melanie Warner’s Pandora’s Lunchbox: How Processed Food Took Over the American Meal, which takes a look at “how decades of food science have resulted in the cheapest, most abundant, most addictive, and most nutritionally inferior food in the world.”

Of course, we eventually do pay a price when we make such products the foundation of our diet – through our health and the cost of medical care for the chronic conditions that are fueled by such a nutritionally empty diet. And as Warner shows, it’s not just because of the usual suspects – process cheese, sugary cereals, chicken nuggets and other “pink slime” products, and the like – but many “healthier” food products, as well.

For the problem with industrial processing isn’t just that they put in a lot of ingredients that our bodies just weren’t designed to accept – artificial colors, flavors and other additives, GMOs and so on. Market needs (products that stay “fresh” for many months, for instance) and the mechanical action of industrial processing strip out much of what was living and nutritious in the whole foods that products are derived from: vitamins, minerals, phytochemicals, enzymes and fiber.

This is why the food companies will then add all kinds of nutrients after the fact. Sometimes, of course, they’ll add supplements that were never in the food to begin with (or were present in very low quantities), creating a seductive health halo by promising the benefits of omega 3s or calcium or probiotics or antioxidants or name your super-ingredient.

It’s not about nutrition; it’s about marketing.

And that’s one of the morals of the second of these recommended reads: Michael Moss’ Salt, Sugar, Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us. While the information about how products are designed to hook us is interesting (if redundant, following Warner’s book), it’s how they’re sold that packs the real punch: how, for instance, Oscar Mayer exploited “kid power” and reversed its declining fortunes by making processed meat “fun” via its Lunchables line.

Moss’ reporting on industry politicking and manipulation speaks loudly, but there’s one detail he repeats several times that speaks volumes: the fact that many food company execs avoid eating – or letting their family eat – their own products, preferring healthier, whole food-based fare. It’s a consistent reminder that these corporations are not, despite what their ad campaigns might depict, interested in providing good food. They exist, as all corporations do, to turn ever larger profits. And they’ll do so in any way they can.

There is one downside to this book: By demonizing the three ingredients named in his title, Moss seems to gloss over all the other problem and suspect ingredients that are put into products called food. In and of themselves, salt and fat are not necessarily bad. What kind of salt and what kind of fat and how much matter a lot more – as well as what they’re combined with, which is often chemical, synthetic and not always thoroughly tested for safety before being put into the food supply.

At the opposite end of the spectrum is the kind of food preparation explored by Michael Pollan in Cooked: A Natural History of Transformation, in which he explores four traditional cooking methods he aligns with the elements: roasting (fire), baking (air), braising (water) and fermentation (earth). Doing so, he vividly shows how cooking puts us in touch the with Earth, connecting us with life cycles and the source of our nourishment. He reminds us that this is the world we come from – not bright and noisy modern world that justifies processed food as “necessity” but the natural world of elements, seasons, change.

Cooking also connects us with each other.

One of the most telling episodes comes toward the end, where Pollan describes his family’s experiment of eating a processed dinner, which he refers to as “Microwave Night.” [Note from Dr. Glaros: “I don’t use or believe it is healthy to use a microwave oven. I believe it stimulates the molecules in an unnatural and unhealthy manner, thus making the food a burden on one’s system to digest.”] The passage deserves to be quoted at length:

The total for the three of us came to $27 – more than I would have expected. Some of the entrees, like Isaac’s stir-fry, promised to feed more than one person, but this seemed doubtful given the portion size. Later that week I went to the farmers’ market and found that with $27 I could easily buy a couple pounds of an inexpensive cut of grass-fed beef and enough vegetables to make a braise that would feed the three of us for at least one night and probably two…. So there was a price to pay for letting the team of P.F. Chang, Stouffer’s, Safeway, and Amy’s cook our dinner.

* * *

Microwave Night turned out to be one of the most disjointed family dinners we have had since Isaac was a toddler. The three of us never quite got to sit down at the table all at once. The best we could manage was to overlap for several minutes at a time, since one or another of us was constantly having to get up to check the microwave or the stovetop (where Isaac had moved his stir-fry after the microwave got backed up). All told, the meal took a total of thirty-seven minutes to defrost and heat up (not counting reheating), easily enough time to make a respectable homemade dinner. It made me think Harry Balzer might be right to attribute the triumph of this kind of eating to laziness and a lack of skills or confidence, or a desire to eat lots of different things, rather than a genuine lack of time. That we hadn’t saved much at all.

The fact that each of us was eating something different completely altered the experience of (speaking loosely) eating together. Beginning in the supermarket, the food industry had cleverly segmented us, by marketing a different kind of food to each demographic in the household (if I may so refer to my family), the better to sell us more of it. Individualism is always good for sales, sharing much less so. But the segmentation continued through the serial microwaving and the unsynchronized eating. At the table, we were each preoccupied with our own entrée, making sure it was hot and trying to decide how successfully it simulated the dish it purported to be and if we really liked it. Very little about this meal was shared: the single-serving portions served to disconnect us from one another, nearly as much as from the origins of this food, which, beyond the familiar logos, we could only guess at. Microwave Night was a notably individualistic experience, marked by centrifugal energies, a certain opaqueness, and, after it was all over, a remarkable quantity of trash. It was, in other words, a lot like modern life.

If you only have time or inclination to read one of these three books, Pollan’s is the one.

Watch “Navigating the Supermarket Aisles with Michael Pollan and Michael Moss.”